Our Quantum Advantage challenge with $20,000 BTC award is live.

More Details →

Here's the problem with most quantum advantage claims: they're nearly impossible to verify.

Take Google's 2019 Sycamore experiment or the recent Willow demonstrations. These systems can likely outperform classical computers—but how do you prove it? The verification process itself requires exponentially expensive classical computation. You're essentially asking someone to trust that you've achieved something they can't check.

In our new work at BlueQubit, collaborating with a researcher at the University of Toronto, we introduce a different approach: peaked circuits. The quantum computer solves the problem in under two hours. The classical estimate? Years on a supercomputer. And here's the key difference: verification is trivial.

Think of a normal quantum circuit like a distribution of bitstrings. With 56 qubits, there are 2^56 possible output bitstrings—about 72 quadrillion possibilities. In a truly random circuit, each outcome appears with roughly equal probability: about 1 in 72 quadrillion.

A peaked circuit changes the game. One specific bitstring—the "peak"—appears with anomalously high probability. For example, a peak may appear about 10% of the time instead of once in 72 quadrillion.

This creates an elegant verification protocol:

No exponential classical computation required. Just check if the answer is right.

The trick is that the circuit must satisfy three crucial properties:

Think of it like a cryptographic hash function, but for quantum circuits. Easy to verify, hard to reverse-engineer. While standard peaked circuits have already been studied and suggested, we suggest and implement harder circuits that go beyond the depth and qubit counts of those previously studied. We call these HQAP (Heuristic Quantum Advantage Peaked) circuits, as they demonstrate a large heuristic gap between classical and quantum runtimes for solving them, and we claim these to be our unbreakable circuits.

The construction starts simple: create a shallow random circuit R, then add a "peaking layer" P that concentrates probability on your target bitstring. But shallow circuits are easy to simulate classically. To make them more difficult, you need to scale them up.

Our solution uses three key obfuscation techniques:

Insert a block that does nothing overall: apply some quantum operation U, and then immediately apply its inverse U-1. Mathematically, the two cancel out, so the whole block is just the identity—it has no effect on the computation.

The twist is that recognizing this fact is extremely hard. Determining whether a given quantum circuit is exactly equivalent to the identity is QMA-complete, even when the circuit is very shallow.

Roughly speaking, QMA-complete means “about as hard as the hardest problems that a quantum computer can efficiently check but not necessarily solve.” It’s the quantum analogue of NP-complete in classical computing. If you could efficiently solve a QMA-complete problem, you could efficiently solve all problems in that class.

So even though the inserted block mathematically does nothing, detecting that it does nothing is believed to be computationally intractable. To an algorithm analyzing the circuit, the extra gates may look meaningful—even though, in principle, they cancel out perfectly.

Of course, naively implementing U then U gate-by-gate would be obvious to detect heuristically. So they scramble it.

Apply a series of SWAP gates throughout the circuit, effectively permuting which qubits talk to which. Since the initial state |00...0⟩ is invariant under permutations, you can ignore SWAPs at the beginning. But in the middle of the circuit, they make it much harder to find efficient tensor network representations or simplify the structure.

The swaps need careful coordination. You can't just randomly insert them, but they dramatically increase the difficulty of classical simulation.

This technique has two flavors:

Angle sweeping: Take a subcircuit with certain gate parameters, then train a new set of parameters that reproduces the same unitary. The result looks different but behaves identically (or nearly so). This hides correlations that might reveal the circuit structure.

Masking: Replace a subcircuit with a different set of gates that approximates the original behavior. Same unitary, different implementation. This breaks up recognizable patterns.

Both make it harder to reverse-engineer the construction or find simplifications.

The magic is in how these techniques combine. Note that to enhance clarity in representing the sequential application of quantum operations, we introduce the left-to-right composition operator ▷, defined by:

U1▷U2▷U3:=U3U2U1

To construct our HQAP circuits we go through the following procedure. You start with:

R ▷ P (a shallow peaked circuit)

Then insert the identity:

R ▷ U ▷ U ▷ P

Then apply sweeping, masking, and swaps. Call this collective transformation T:

T[R] ▷ T[U] ▷ U ▷ P

The result looks like a random circuit with all-to-all connectivity. But it's carefully constructed to concentrate on one specific output bitstring.

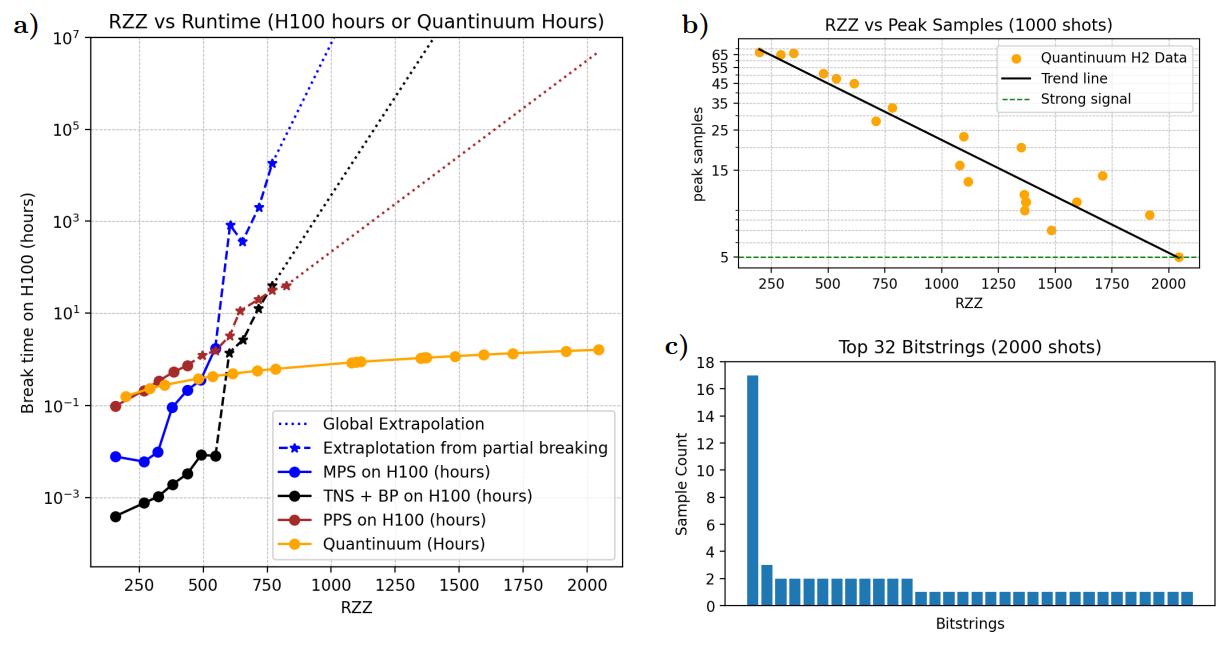

We threw everything at these circuits: thousands of A100 and H100 GPU hours, tens of thousands of CPU hours, and the best classical simulation techniques available.

MPS works well for 1D systems with local interactions. But these circuits have all-to-all connectivity—essentially the worst case for MPS. Still, it's worth trying because a low-rank MPS might accidentally reproduce the peak without capturing the full state.

For circuits up to ~600 two-qubit gates, MPS succeeded. Beyond that, they failed.

The memory requirement (bond dimension ) grows exponentially with circuit depth. We tracked both and simulation time as functions of gate count. For our largest circuits, even with maximal bond dimension max 108, MPS cannot crack the circuit.

A more sophisticated approach: represent the state as a general tensor network, then use belief propagation to compute marginals (the probability each qubit is 0 or 1). If the peak is strong enough, these marginals should point to the right answer.

The challenge: all-to-all connectivity means a high coordination number, making tensor operations expensive. The solution: transpile to a simpler topology (they used a tree structure), then simulate that.

This worked better than MPS—solving circuits up to ~700 gates—but still hit an exponential wall. Our estimates suggest the largest circuits would take 300 million GPU hours.

This newer technique evolves Pauli operators backward through the circuit, truncating low-weight terms. It's been remarkably successful at simulating noisy quantum circuits.

PPS worked well in the shallow regime, solving all qubits for circuits with up to 388 RZZ gates. But memory quickly became the bottleneck. They could track about 1 billion Pauli strings before running out of RAM on an H100 GPU.

For deeper circuits, we developed a "relative truncation" method that dynamically adjusts thresholds. This helped, but couldn't overcome the fundamental scaling issue.

Beyond brute-force simulation, we tested attacks that exploit the circuit construction:

Angle correlation: In a naive U ▷ U circuit, gate angles in the second half mirror the first half. Angle sweeping successfully hides these correlations after a few rounds.

Connectivity patterns: You might reveal the permutation by matching which qubit pairs interact. But combined with masking (which changes the connectivity), this becomes a more difficult version of graph isomorphism—an already NP problem.

Transpiler simplifications: Modern transpilers like Qiskit's can often simplify circuits by detecting cancellations. We found that even a few swap bottlenecks prevent most simplifications. A naive identity circuit gets completely eliminated, but after scrambling, most gates survive.

Middle MPO attack: Start with an MPO (matrix product operator) representing the identity in the middle of the circuit, then evolve gates on both sides. For a naive identity block, this compresses easily. But the combination of sweeping, masking, and swaps prevents compression. The boundary between T[U] and U effectively disappears.

While classical methods struggled, Quantinuum's H2 processor handled our circuits efficiently.

Our largest test: 56 qubits, 2044 two-qubit gates, all-to-all connectivity, peak weight ~10%.

H2's performance:

For a 1917 RZZ circuit, we measured 17 correct peaked bitstrings out of 2000 shots. The signal is noisy but clear.

The verification is straightforward: count how many times the known peak appears. With 10% peak weight, you expect it roughly 200 times per 2000 shots. Instead, you get ~17 times due to noise. But this is still orders of magnitude above the ~10^-16 you'd expect for a random bitstring.

"To our knowledge, no other device in the world can find the peak for HQAP circuits of this scale and connectivity."

Let's put the numbers in context:

Quantum (H2): <2 hours

Classical methods (extrapolated):

For a 2000-gate circuit, even running on exascale systems like Frontier or Summit, classical methods would take years.

Of course, these are extrapolations. The classical algorithms fail to find the correct answer beyond ~700 gates, so the estimates for deeper circuits involve fitting exponential curves and projecting forward. But the trend is consistent across all three methods.

We're careful to call this "heuristic quantum advantage" rather than verifiable quantum advantage. Why?

We can show that a closely related task is also computationally hard. In particular, deciding whether an arbitrary quantum circuit is peaked—when you don’t know the input state or the output in advance—is QCMA-complete.

Informally, QCMA-complete means the problem sits at the very edge of what we believe is efficiently solvable, even with quantum computers. A proposed solution can be checked efficiently by a quantum computer (with a classical bitstring witness as opposed to a quantum state for QMA-complete problems), but actually finding or deciding the solution is believed to be infeasible in general.

You can think of it as the quantum version of “someone can give you a convincing classical hint that the answer is yes, and a quantum computer can verify it quickly—but without that hint, there’s no known efficient way to figure it out.” Under standard complexity assumptions, this means that even quantum computers aren’t expected to solve this problem efficiently.

But we can't prove our specific construction is hard to simulate classically. There's no formal reduction from a known hard problem to "find the peaked bitstring in this specific HQAP circuit."

This is similar to RSA in classical cryptography. We can't prove factoring is hard. There's no proof that P NP, and even if there were, it wouldn't necessarily imply factoring is hard. Yet after 40+ years of failed attempts, including explicit challenges with prize money, the community treats RSA's hardness as an empirical fact.

We take a similar stance: "Just as the hardness of factoring large integers is widely believed, despite the lack of a formal proof, because of decades of failed attempts to break it, the intractability of simulating peaked circuits may come to be seen as an empirical fact."

The hardness results suggest an intriguing application: post-quantum encryption.

Standard post-quantum cryptography (like the NIST standards ML-KEM and ML-DSA) consists of classical algorithms believed to resist quantum attacks. They run on today's computers and networks.

Peaked circuits offer something different: encryption that requires a quantum computer to decrypt.

The protocol sketch:

Security reduces to two assumptions:

This gives three unique properties that other post-quantum schemes lack:

Receiver-local validity: You can verify correct decryption just by checking the measured peak weight. If someone sends you a malformed ciphertext, you'll know immediately.

Proof of quantum access: Decryption inherently proves you have a working quantum computer. This could be valuable for protocols that need to verify quantum capabilities.

Truly quantum: Unlike NIST's post-quantum standards, which are classical algorithms, this approach fundamentally requires quantum hardware.

Of course, this is still speculative. The security relies on an unproven "Peak-Search Hardness" conjecture. But if HQAP circuits are indeed classically hard to solve, this could open interesting new directions in quantum cryptography.

This work represents a maturing of the quantum advantage narrative.

Early demonstrations like Sycamore were important milestones, but they suffered from a verification problem. You had to trust exponentially expensive cross-entropy benchmarking, which becomes impossible at scale.

Recent utility-scale experiments from IBM, Google's Willow, and Quantinuum's H2 pushed random circuit sampling to impressive scales. But the verification problem remains.

Peaked circuits offer a different path: empirical quantum advantage with efficient verification.

Can we prove these specific circuits are hard? No.

Can we prove similar circuits are hard? Yes—QCMA-completeness for the decision problem.

Have all known classical methods failed? Yes—after thousands of GPU hours and three state-of-the-art approaches.

This is the pattern of mature engineering: you build something that works in practice, you understand the theory around it, and you invite scrutiny. If it survives years of attempts to break it, confidence grows.

As we put it in the paper: "In the absence of such breakthroughs, we view these circuits as offering a valuable benchmark for the quantum community. They provide a target that is both meaningful and falsifiable—anyone who can simulate them classically is encouraged to do so."

We've made our circuits publicly available at the "BlueQubit Peak Portal" and invited the community to try breaking them.

We're moving from "quantum advantage you have to trust" to "quantum advantage you can verify."

Like the RSA Challenges of the 1990s and 2000s, we've announced an open-peaked circuits challenge. We're releasing increasingly difficult circuits and inviting anyone to submit classical solutions.

The RSA challenges were never formally proven hard. But they built empirical conviction through sustained community effort. If our peaked circuits survive similar scrutiny, they may achieve similar status: practically hard, even if theoretically unproven.

So if you have access to a supercomputer and a clever classical algorithm, the gauntlet has been thrown down. The circuits are public. The verification is simple.

Can you find the peak?

The research paper "Heuristic Quantum Advantage with Peaked Circuits" is available on arXiv at 2510.25838. Circuits are available at the BlueQubit Peak Portal.